Janet Stephenson

Dr Janet Stephenson is a social scientist with a particular interest in societal responses to environmental challenges. She is the Director of the Centre for Sustainability at the University of Otago, which carries out interdisciplinary collaborative research in agriculture, food, energy and environment (www.csafe.org.nz)

The Blueskin Resilient Community

Posted on 13 June 2013

by Janet Stephenson

My first encounter with the Waitati community was in 2007, when I brought a small group of young planning students to meet with some Waitati residents. They were asked to find out first hand about the community’s perspectives on the future sustainability of the settlement. Climate change and energy security were top issues, as well as food and transport. The students were given free rein to develop creative ideas about how the community could respond to these challenges. Then we came along to the Waitati Hall one evening, where the students each gave a brief presentation. I was absolutely astonished at how many people turned up – around 60, I recall. The community members took a kindly interest in the (sometimes wacky) ideas that the students came up with, but underlying this was a strong sense of a collective purpose and urgency to take action on sustainability issues. I came away from the session with the feeling that this community could do something extraordinary.

Fast forward six years, and extraordinary things have been achieved[1]. Initiatives like Waitati Edible Gardens and Waitati Open Orchards have strengthened local food production. Get The Train and the rideshare scheme aim to reduce individualised commuting, and a local innovator is designing and producing cutting-edge retrofit electric vehicles. Many cold houses have been made warmer through an insulation scheme and home energy advice run by the Blueskin Resilient Communities Trust. Fifty households have come together to collectively order photovoltaic systems. Huge progress has been made towards developing New Zealand’s first community-initiated wind cluster. And the list could go on.

What’s particularly impressive is that this began as just a few people talking about resilience in the wake of the 2006 Waitati flood, but has increasingly gathered community support and rippled outwards into other communities. Suddenly we’re all talking about ‘Blueskin’ to refer to the communities that run from Purakaunui right up towards Seacliff. That name wasn’t used in this way until the Blueskin Resilient Communities Trust started to draw together these communities in developing a vision for their collective future. And those ripples go further, now influencing the wider Dunedin community and businesses, the Dunedin City Council, and inspiring other communities nationally.

As a social researcher with a particular interest in sustainability transitions, I am intensely interested in how this change in Blueskin is occurring, and its implications, especially in the area of energy behaviour. A lot of my research at the momement is on something we’ve called Energy Cultures, and what it takes to shift ‘locked-in’ unsustainable behaviour in households, businesses and transport. And looking at Blueskin with an Energy Cultures perspective helps me understand just why that 2006 aspiration has so effectively rippled out to become a stellar example of a community in transition.

The Energy Cultures framework is a way of thinking about behaviour. It might be to do with how you use energy in your home, but it might also be about how you travel, or how you run your business. We can talk about your personal energy culture, or about a group energy culture where you get a whole lot of people behaving in a similar way. We can even talk about the energy culture of New Zealand compared to other countries – for example, who hasn’t had an international visitor complain about how cold we keep our houses?

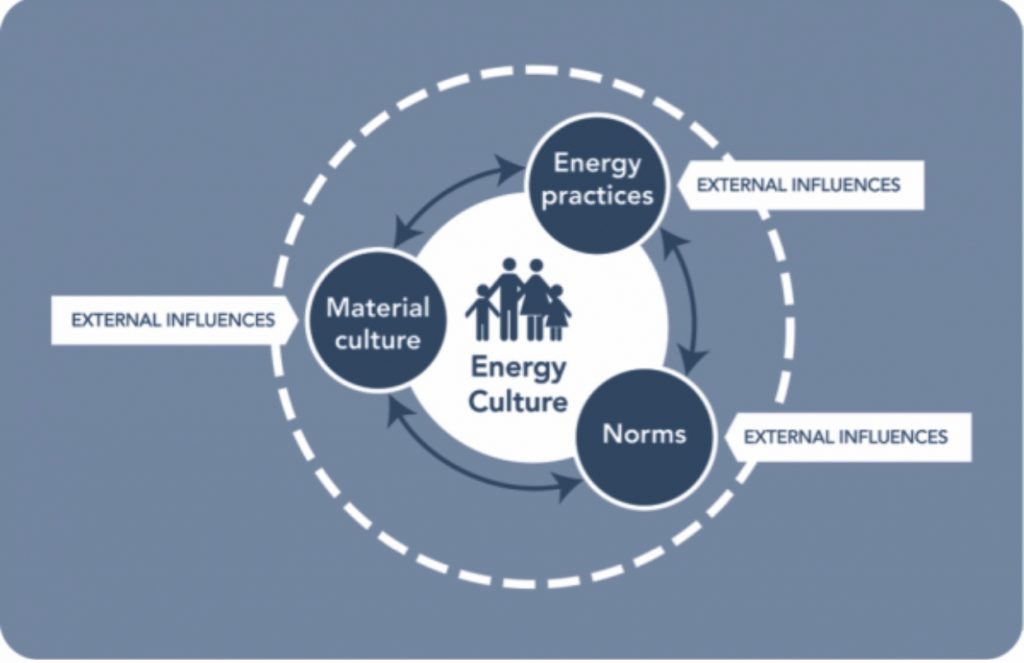

We use the word ‘culture’ because in defining a culture you look for distinctive patterns in what a group of people have (their ‘material culture’), what they do (their ‘practices’) and how they think (their ‘norms’). Applying this to my own life, our own ‘energy culture’ around heating at home (until recently) consisted of an un-insulated, cold house with inefficient heating (our material culture); only heating one or two rooms, and wearing lots of woolly layers inside (our practices); and expecting to be cold indoors (our norms). As you can see, these things reinforced each other so that we had a habitual pattern of heating behaviour: a rather frugal and inefficient energy culture.

But at the same time, we weren’t really happy with this situation. We had developed aspirations to use energy more efficiently and to be warmer at home (our norms were shifting), and this was inspired in part by what was happening at Blueskin, and also by having an energy audit that helped us see what was possible (external influences on our norms). Thanks to the Warm Up New Zealand subsidy, we were able to get insulation put in, and when a dear relative left us some money, we could afford to put in a new heating system (external influences on our material culture). And we learnt from a workshop about the importance of curtains to keep the heat in, so we’re now fastidious about pulling the curtains in the early evening (external influence on our practices). And now our energy culture is quite different, our house is warmer, and our energy bills are lower!

Looking at what’s been happening in the Blueskin area, it is clear that there are big shifts happening in the ‘energy culture’ of individual households, and also in the energy culture of the communities more generally. If you compare to say 5 years ago, who would have anticipated that over 400 households in the Blueskin (and wider) area would be insulated through the BRCT insulation retrofit programme? That over a hundred people would attend an energy expo at the hall? That 50 households would come together to purchase PV for their roofs? Or that there would be such a strong groundswell of support for a wind turbine cluster?

I believe that this widespread shift to a more sustainable energy culture wouldn’t have happened if the BRCT movers and shakers had only tried to make people better informed about energy. Or only worked on improving housing quality. Or only tried to get people to use energy efficiently. The reason it has worked so well is that the BRCT’s activities have brought about changes in norms and practices and material culture, all at the same time, and in a way so that each supports the other. And BRCT has also seized opportunities to channel other external influences that have supported the community’s changing energy culture, such as the free home energy advice, the subsidised retrofit programme, and the wind cluster consultation process.

And then there’s the ripple effect that I mentioned earlier. Our research elsewhere has shown that people’s energy decision-making is most strongly influenced by their family and friends. We found that people’s social networks were around 3 times more influential than all media (including TV ads) and 4 times more influential than all organisations (including energy companies, council and trades). And people talk about energy a lot, especially in Waitati! Our household survey there in 2008 showed around 45% had energy-related conversations at least weekly, and around 16% had energy-related conversations at least once a day! As people talk about their aspiration to change, make the change, and show others what they’ve achieved, they influence others to think: “actually, I could do that too…”. So the shifts in individual energy cultures become a new external influence towards change in others’ energy cultures. The ripples go on …

One of the other research projects I’m involved in is called Green Grid, with a team from Otago, Canterbury and Auckland universities that is looking at the requirements for a future ‘smart grid’ for New Zealand. The problem is how New Zealand’s electricity grid might operate in a future that includes 90% or more renewable generation (currently it is about 75-80%), increasing amounts of distributed generation (especially from PV on homes) and possibly electric vehicles both drawing from and feeding into the grid. This mix together could make for a much more volatile and complex supply and demand situation than at present.

The idea of being a ‘prosumer’ – someone who both produces and consumes energy – was pretty much un-thought of in the general population a few years ago. When we were developing the proposal for the Green Grid research some 18 months ago, the idea of there being whole communities that would be generating their own energy and potentially pumping it back into the grid seemed far off and theoretical. But Blueskin is rapidly pushing this to reality, and the ripple efffect of this energy culture shift may help us understand how infrastructure and grid management may need to change if the prosumer trend is taken up widely. For example, if you are producing your own electricity through PV, and feeding back into the grid, will you use more or less energy in total, and will you change the time of day when you carry out energy-using activities?

So I look at Blueskin with huge admiration: a group of diverse communities, households and individuals who have come together to develop a shared vision about how to transition to greater local resilience … and are actually making it happen.

I’ll leave you with a challenge. As I see it, the Blueskin community has been incredibly successful in building momentum to change household energy cultures. Much less has been achieved in changing the transport culture, which is still heavily reliant on single-occupancy fossil-fuel powered cars. How about looking at the transport situation through the energy cultures framework? This would lead you to ask questions like: What is the current material culture (vehicles, infrastructure, public transport provision etc)? What are current practices? What are current norms? Can we see some distinctive energy cultures in Blueskin? What external influences are creating an undesirable ‘lock-in’? And then, what are people’s aspirations, and how might you build on these to start re-visioning a more resilient transport culture for Blueskin? And then, what external influences could you call on to help shift norms, material culture and practices to achieve a widespread transport transition?

I’ll leave the last word to one of my students from that 2007 planning exercise, in which they were asked to state their vision for a sustainable Waitati in 2017 (not so far away now!):

“Waitati in 2017 will be equipped with a process of genuine community collaboration to ensure thoughtful and inclusive decision-making. This process will be supported by Local Government authorities over time as the wisdom of ‘local initiatives finding solutions to local issues’ is recognised. Expected outcomes include a heightened sense of civic responsibility, ownership and trust, not only in the participation process but also in the physical outcomes”

Janet Stephenson

19 May 2013